Alexandra Palace’s Curator and Heritage Manager, Kirsten Forrest has collaborated with Ally Pally volunteer and Open University Honorary Lecturer Roger Hancock, to carry out a year-long study looking back at the Open University (OU) production unit housed in Ally Pally from 1970-81, including memories from many of those who worked here.

These interviews and other research, initially conceived for a 50th Anniversary exhibition, will form part of the Alexandra Palace Archive Collections Online and are intended to be shared with our BBC archive partners, Google Arts & Culture and across the wider heritage community.

The beginnings

The OU was established in 1969, primarily as a new kind of distance learning. The Queen granted a royal charter to this university focused on “mature students” (over 21s), those who had missed the opportunity of attending a university at 18, and many who may not have considered traditional higher education or studying for a degree.

Geoffrey Crowther, the first OU chancellor, addressed this in 1969 at the charter ceremony:

‘The first and most urgent task before us, is to cater for the many thousands of people fully capable of a higher education, who for one reason or another, do not get it, or do not get as much of it as they can turn to advantage, or as they discover sometimes too late, that they need. . . The existing system for all its great expansion misses and leaves aside a great unused reservoir of human talent and potential.’ (Crowther, 1969)

Choosing Ally Pally

While the OU’s administrative base was in Milton Keynes, it required studios to produce and broadcast its programme of studies for students.

A number of existing BBC studio centres were considered by the OU’s executive in 1968/69. A key issue was distance from Milton Keynes – up to an hour was regarded as viable. The Palace, although at the time run down in many ways, was well placed for the M1 and seen as adaptable with its two studio spaces. These dated back to 1936, when they were used for the world’s first regular high-definition public television broadcast. Moreover, BBC News was still operating there. With a sense of urgency to provide the first four foundation courses for students, BBC/Open University Productions moved in to Ally Pally, early in 1970.

Using the BBC studios

Benetta Adamson, who first joined the BBC at Broadcasting House as a trainee after her ‘A’ Levels, worked at the Palace as a production assistant. She remembers:

‘It was a shanty town inside the old Palace. The tower was really the only bit which felt as if it more or less had the function intended. Everywhere else was make-do and mend’. (Adamson, 2019)

Tony Coe (2019), a BBC radio producer, remembers the premises as being higgledy piggledy but it also had a feeling of being ‘really interesting, dynamic, and almost a law unto itself’

The history of BBC broadcasting at the Palace created a significant and historically charged atmosphere for those who were appointed to be there in the 1970s. In a sense, the choice of Alexandra Palace was revisiting history. Just as the newly formed BBC moved into the Palace and adapted the premises in 1936, so the newly chartered Open University tailored the premises for its purposes in 1970.

John Hulse, a sound engineer, recalls:

‘I felt very much at home there as it’s steeped in history. I loved exploring the building and finding clues as to how television started because there were plenty of clues around in terms of hardware and mysterious doors and things.’ (Hulse, 2019)

It made a similar impression on Tricia Cann:

‘It’s an iconic and a most amazing place to work, it really was. It had a kind of intimacy that did inspire people.’ (Cann, 2019)

Using what was there

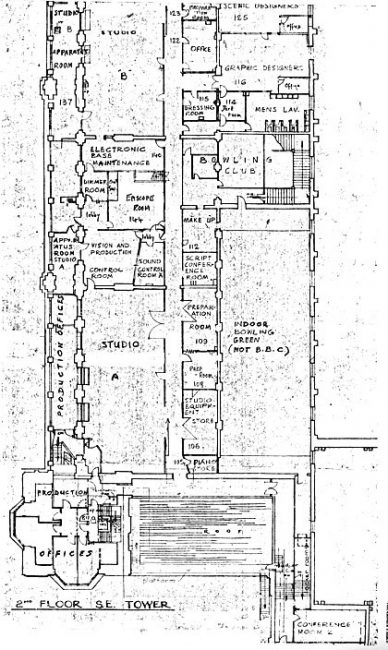

The plan below shows the complex of corridors, connective spaces and rooms including the two studios to the left marked ‘Studio A and B’. The designated Studio A needed some refurbishment and re-equipping, as did the nearby technical areas and the offices. Studio A was challengingly narrow, given it was just 30 x 70 feet, but was larger than Studio B which was mainly used for rehearsals and storage.

David Kennard, deputy to Bob Rowland (head of BBC/OU Production at the Palace), mentions the specific resources available for production at the Palace in 1970. He itemised three monochrome cameras, two pairs of Ampex two-inch video-tape recorders, one Telecine (for film and slide projection), four film cutting rooms, a ‘prep’ lab, a small visual effects unit, and a photographic studio with black-and-white processing facilities (Kennard, 1980).

With regard to this studio, John Hulse, a sound engineer, recalls:

‘We had great fun trying to produce dramas in the studio that was a shoe box.’ (Hulse, 2019)

Below the ground floor were various BBC occupied basement areas which, from 1936, were used for storage, cutting rooms and laboratories. A little away from the central production area was the East Court which was used for various support functions.

(Outside broadcast/radio vans, East Court, May 1981, just before the move to Milton Keynes – copyright unknown)

Sound recording was located in a room that was close to the Great Hall. John Hulse recalls an unexpected problem:

‘I remember once we were in the radio studio and we couldn’t record anything that day because Pink Floyd had hired the Great Hall and they were rehearsing for their next concert. Their sound just went straight through the wall’. (Hulse, 2019)

It wasn’t just Pink Floyd! As with all other BBC locations across London, the Palace had a club and bar. This was a popular place and the social heart of the production community. It had a reputation for having a particularly convivial atmosphere. It also had a snooker table, a pool table, and darts accessed through sliding doors. Competition, by all accounts, could be intense. Ian Macdonald, a dark room print finisher, states:

‘My favourite memory is that just before the Milton Keynes move Nationwide programme came from there [the Palace]. The studio was above the bar and we were told to keep the noise down as they could hear us up there.’ (Macdonald, 2019)

OU success

To the surprise of many (and the envy of most established universities) there were some 43,000 applicants for the first four foundation courses resulting in 25,000 registered students. To put this into perspective, in 1970 the total number of graduates from all UK universities was 51,189 (Bolton, 2012).

Three years after the OU productions were installed at the Palace the University held its first graduation ceremony. It was attended by 867 graduates plus their families and friends.

(the first graduation ceremony on 23rd June 1973 – copyright Open University Library Digital Archives)

A staff list dated 19th February 1974, gives the number of persons employed as 306, and this doesn’t include OU academic staff because they would have visited only when they were directly involved in planning or presenting radio or TV materials. The staff list identifies a considerable variety of production and support roles – designers and graphic artists, maintenance staff, secretaries and typists, production directors, firemen, assistants, riggers, film editors, electricians, porters and lift attendants, telephone operators, cleaning staff, engineers, post room staff, research assistants and heads/senior staff. This list is revealing of the workforce that was needed to produce and broadcast the twice weekly radio and TV programmes. OU productions also co-opted top names to appear in their productions, such as Ben Kingsley and Patrick Stewart.

The 1980 fire

(Copyright Roy Chivers)

Alan Bird was on duty on that ill-fated day and reports:

‘Alan Cathie [senior television engineer] was on the phone trying to raise the fire brigade. I went down the stairs and switched the studio power off in the middle of a programme. It was obviously not just a puff of smoke so we did evacuate the building’. (Bird, 2019)

Tricia Cann, also at work, remembers that having enrolled as an OU student, she’d left her nearly completed social science foundation assignment on her desk when the fire bell sounded. She assumed, like many, that it was only a fire drill. When assembled outside with others, she noted helicopters overhead and the west side roof of the Palace on fire.

John McCafferty, who worked in the post room, had gone to his nearby home for lunch. When he looked out of the living room window, he could see a plume of smoke. Preparations were being made for an open-air jazz weekend by Capital Radio, so at first John thought a stage light might have caught on fire. John also recalled that a video tape store was close to the Great Hall. A human chain was formed to remove pre-recorded OU programmes, put them in a car and then transport them to a nearby garage as a temporary measure.

The intense fire that destroyed the Palm Court to the west, the Great Hall, the Banqueting Suite, the former roller-skating rink, and the theatre dressing rooms, failed to reach the BBC/OU production areas, the East Court, or the Victorian theatre. Ironically, the survival of the BBC wing was down to a literal firewall that the Palace management had insisted BBC install to protect the Victorian building from the fire risk of dangerous television equipment back in 1936!

Saying goodbye to the Palace

In July 1981 those still working at the Palace were relocated to the OU’s purpose-built studios and production facilities on campus at Milton Keynes.

‘One of the main aims we had in the move to Milton Keynes was to try and bring with us the spirit of Ally Pally’. (Rowland, 2009)

(OU/BBC staff prior to the last day of working on July 3rd 1981 – copyright unknown)

Nancy Thomas, BBC arts producer (standing centrally, front row, with a white scarf) writes in a Newsletter on 17th June 1981:

‘The great exodus, after so much anticipation, is finally upon us. The last working day is July the 3rd – and there is to be a party that evening in the Club. Weather permitting David Amy [photographer] wants everyone by the miniature golf course at 3.00 p.m. precisely for a final family snapshot in front of the Palace . . . I wish you well in your new home and hope not to lose touch completely’. (Thomas, 1981)

In the light of this development half a century ago, it is currently of interest, given Covid-19, that Cambridge University, a long-established face-to-face institution, has decided to offer much of its teaching online for the 2020-21 academic year.

You can read Kirsten and Roger’s full study here